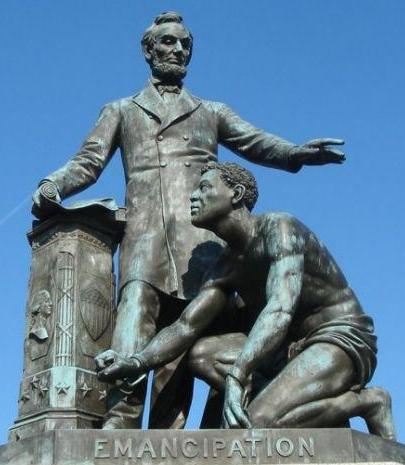

Paid for by freed slaves, the Emancipation Memorial, more popularly known as the Freedmen's Monument, was dedicated in Lincoln Park on Capitol Hill on April 14, 1876, the eleventh anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln's assassination. In attendance for the event was President Ulysses S Grant, along with a mixed audience of white and black.

Paid for by freed slaves, the Emancipation Memorial, more popularly known as the Freedmen's Monument, was dedicated in Lincoln Park on Capitol Hill on April 14, 1876, the eleventh anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln's assassination. In attendance for the event was President Ulysses S Grant, along with a mixed audience of white and black. The dedication speech was given by Frederick Douglass. Douglass and Lincoln met three times during the Civil War and their relationship (a relationship THC has previously written about) was complex with the initial wariness of Douglass giving way to admiration. In his speech, Douglass, a brilliant orator and a brilliant man, tried to honor Lincoln while at the same time attempting to explain white and black to each other, using Lincoln to do so. He was also trying (unsuccessfully) to prompt stronger federal reaction to violence against the freed slaves in the South.

Below are some excerpts from the speech, along with THC's attempt to make some comments but the entire speech makes for rewarding reading because the complexity of its theme is hard to convey by excerpts.

To the extent the speech is still remembered today it is for these two passages:

He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country . . . You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his step-children; children by adoption, children by forces of circumstances and necessity.

------------These observations tie back to Douglass' starting point - the different worlds inhabited by blacks (even those free before the war) and whites. Early in his speech he uses the occasion to comment on the changes since the war as well as noting the remaining dangers:

Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.

Harmless, beautiful, proper, and praiseworthy as this demonstration is, I cannot forget that no such demonstration would have been tolerated here twenty years ago. The spirit of slavery and barbarism, which still lingers to blight and destroy in some dark and distant parts of our country, would have made our assembling here the signal and excuse for opening upon us all the flood-gates of wrath and violence.He then goes on to praise the occasion with perhaps a note of false, but necessary optimism in light of the continued lack of acceptance of freed blacks:

I refer to the past not in malice, for this is no day for malice; but simply to place more distinctly in front the gratifying and glorious change which has come both to our white fellow-citizens and ourselves, and to congratulate all upon the contrast between now and then; the new dispensation of freedom with its thousand blessings to both races, and the old dispensation of slavery with its ten thousand evils to both races — white and black.Douglass moves on to the purpose of the monument, that:

those of aftercoming generations may read, something of the exalted character and great works of Abraham Lincoln, the first martyr President of the United States.It is then that he moves on to his startling proposition (at least to his white audience):

Truth is proper and beautiful at all times and in all places, and it is never more proper and beautiful in any case than when speaking of a great public man whose example is likely to be commended for honor and imitation long after his departure to the solemn shades, the silent continents of eternity. . . Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.After this assertion comes the portion from the first excerpt THC quotes above. But between the ellipses inserted into the abridged remarks, Douglass lays down quite a damning indictment of Lincoln from the black perspective. THC didn't quote it in full because he wants you to read the whole thing!

After filing his charges, Douglass evokes the patience that blacks demonstrated with the man despite the difficulties:

Our faith in him was often taxed and strained to the uttermost, but it never failed. When he tarried long in the mountain; when he strangely told us that we were the cause of the war; when he still more strangely told us that we were to leave the land in which we were born; when he refused to employ our arms in defense of the Union; when, after accepting our services as colored soldiers, he refused to retaliate our murder and torture as colored prisoners; when he told us he would save the Union if he could with slavery; when he revoked the Proclamation of Emancipation of General Fremont . . . Despite the mist and haze that surrounded him; despite the tumult, the hurry, and confusion of the hour, we were able to take a comprehensive view of Abraham Lincoln, and to make reasonable allowance for the circumstances of his position. We saw him, measured him, and estimated him; not by stray utterances to injudicious and tedious delegations, who often tried his patience; not by isolated facts torn from their connection . . . we came to the conclusion that the hour and the man of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln.It is only then that Douglass turns to the realities faced by President Lincoln and his acknowledgement of the wisdom of his strategy:

--------------

Any man can say things that are true of Abraham Lincoln, but no man can say anything that is new of Abraham Lincoln. His personal traits and public acts are better known to the American people than are those of any other man of his age. He was a mystery to no man who saw him and heard him. Though high in position, the humblest could approach him and feel at home in his presence. Though deep, he was transparent; though strong, he was gentle; though decided and pronounced in his convictions, he was tolerant towards those who differed from him, and patient under reproaches.

I have said that President Lincoln was a white man, and shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race. . . His great mission was to accomplish two things: first, to save his country from dismemberment and ruin; and, second, to free his country from the great crime of slavery. To do one or the other, or both, he must have the earnest sympathy and the powerful cooperation of his loyal fellow-countrymen. Without this primary and essential condition to success his efforts must have been vain and utterly fruitless. Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible.That is the point at which Douglass adds the second quote regarding the view "from the general abolition ground". He furthers adds a truthful and meaningful distinction in Lincoln's thoughts:

Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery.He returns again to the criticism faced by Lincoln from all sides:

Few great public men have ever been the victims of fiercer denunciation than Abraham Lincoln was during his administration. He was often wounded in the house of his friends. Reproaches came thick and fast upon him from within and from without, and from opposite quarters. He was assailed by Abolitionists; he was assailed by slave-holders; he was assailed by the men who were for peace at any price; he was assailed by those who were for a more vigorous prosecution of the war; he was assailed for not making the war an abolition war; and he was bitterly assailed for making the war an abolition war.Douglass goes on to contrast Lincoln's predecessor, "the patrician" President Buchanan and his timid approach to the crisis of secession with the steady judgment of "the plebeian" Lincoln and ending the passage with these wonderful sentiments.

The trust that Abraham Lincoln had in himself and in the people was surprising and grand, but it was also enlightened and well founded. He knew the American people better than they knew themselves, and his truth was based upon this knowledge.He closed with these words:

When now it shall be said that the colored man is soulless, that he has no appreciation of benefits or benefactors; when the foul reproach of ingratitude is hurled at us, and it is attempted to scourge us beyond the range of human brotherhood, we may calmly point to the monument we have this day erected to the memory of Abraham Lincoln.Douglass' hopes for a new day in race relations were to be dashed with the onslaught of Jim Crow laws in the South during the 1880s and 1890s, ensuring white supremacy for another three quarters of a century as well as the large scale refusal in the North to accept social equality with blacks and widespread, but more subtle, means of discrimination.

No comments:

Post a Comment